I am very excited to chat with my guest, Dr. Emily King today.

I identify as neurodivergent and Emily identifies as neurotypical, but we've talked about how we both experienced a lot of anxiety in the classroom as kids that followed us into adulthood.

I'm curious to explore that today from a really comprehensive lens. We've worn so many hats at this table. So I love that we can chat from both an educational, parental and experiential perspective.

Performance Anxiety in the classroom

Melissa: Can you share a bit about what school was like for you as a child in the classroom?

Emily: Yeah. So, I was a very teacher-pleasing, perfectionistic student. I was actually four when I started kindergarten. I was the youngest, my mom was working, plus all the cultural variables- so she was like, okay, it's probably time to go to school. And I was academically fine. And that's what we looked at in the 80s, right?

But my memories of school were trying to do everything I needed to do to keep up. There were times when I was seen as an excellent student and times when it was really hard for me.

Sometimes I feel like that is because of my age. I mean, I was almost a whole year younger than many students. And other times I think it was anxiety. I had a lot of performance anxiety that I don't really have anymore (but again, my anxiety is much better treated now than it was when I was, let's say, 8 years old.)

Looking back, it was a lot of anxiety around:

Not wanting to raise my hand

Or not wanting to get called on.

Like, please don't call on me, I don't want to read in front of the class.

Those types of things.

I was a really, really hard worker, and in many ways that served me well. And in many ways, as an adult, I’ve needed to dive into that in therapy and undo that “overworking to prove my worth” narrative.

And that's of course, continuing to evolve as I've worked with kids and families, and seen some of those patterns repeat themselves. So I find the psychology of learning and the emotions that go with it just so fascinating.

Melissa: Yeah, I find it so fascinating too. And what is so interesting to me is you said, you experienced anxiety about raising your hand or being called on to read aloud. And I had that same experience too.

I am dyslexic and have ADHD and I always attribute my school anxiety to my neurodivergence, but yet we're having such a similar experience in similar situations.

I didn't want to raise my hand.

I didn't want to get called on.

And I always thought it was because I was so distractible.

My head would be in the clouds.

So if someone called on me, I'd be embarrassed because I wasn't paying attention or didn't know the next step.

Or sometimes I would get so anxious that if they called on me to read, my brain would almost shut down.

I literally couldn't read the words even though I knew I could read the words, you know? I was a more labored, intentional reader as a child, and was fully able to do the task at hand. But I might just completely blank. And then I get anxious about: “oh no, I'm going to blank in front of everybody and feel embarrassed.”

It's just interesting that we have different neurowirings, but had a similar emotional experience in the classroom environment. Is that a thing for you too?

The Emotional Experience of Anxiety in the Classroom

Emily: Yes, my mind would go blank when I was called on, but it was coming from a place of being judged or making a mistake. And all of these were irrational fears of mine because I could read.

I think I was probably on the lower side of reading. I never had any difficulty reading, but I was very intentional with my reading.

I've always loved writing even more than reading because I feel more in control of writing. So I don't know what that says about me?

But that idea of:

potential embarrassment

or, what if I answer the question wrong?

It was all for me about anxiety. Because without that idea of someone watching or that spotlight on me I could read fine for homework or read silently.

The other interesting part of my story is that: I was always into music and choir. I could get up on a stage and perform with no problem. When we think about the differences between literacy and music in our brain. Music and movement (any type of visual art really) is very systemic and regulating in our nervous system. Once we practice and learn a piece of music, it takes over. And we just do it.

We don't have to think about it, right? And I think that for me, was an outlet. That was a different way of expressing myself that, I didn't feel anxious when I did those things.

Melissa: I know for myself, I can look back and see, I was literally in my survival brain for most of my early years in education. And so I wasn't open and available to even receive the goodness that was coming at me probably because I didn't have access to that part of my brain.

Emily: Yeah, and I think I had moments in my schooling where I was in survival mode, but it looked like pleasing or doing exactly what I needed to do.

When I realized, later in college and graduate school thanks to the scientific method, that I could question things, that you're supposed to have a hypothesis and it's supposed to be wrong sometimes. That's what I needed. That permission.

Not to nerd out a little bit on theory, but with Vygotsky's learning theory, he said: we learn best by taking the just-next-step outside of our learning zone.

If we stay in our learning zone, we're not going to grow. And if we're too far outside of our learning zone, we're not going to be able to reach it.

When I think about that through the lens of nervous system regulation, obviously the farther out we get from our learning zone, the more dysregulated we are, the more everything's over our head. We feel like we're sinking, the panic sets in, you can't learn out there.

And so I think when we get too far outside of our learning zone, we don't feel safe. Sure, we're not, going to be attacked from an evolutionary standpoint but we are wired for safety. We're wired to feel safe and connect and absorb new information when we feel safe and connected.

But if we have an anxious temperament, we may have a threat response to something that, to another person wouldn't feel “dangerous,” but to us it feels so overwhelming. Like speaking up at that moment or asking a question if we don't understand.

Getting Curious Around Our Experiences

Melissa: Yeah. And I think that's where it brings it back to making the assumption that we're all having the same experience to the same environment. Particularly with neurodivergent students in the classroom, they often do have more sensitive nervous systems and they're interpreting the world around them more intensely and more deeply. And there can be barriers to learning, that we might just take for granted if we're not wired in that way.

Emily: I think we are at a space in our history with education where we're starting to get more curious. And if we can keep pushing back a little bit with the kids who can absolutely learn all of this content just in a little bit of a different way. I think that we could have kids and teachers less stressed at school.

Melissa: 100% and reduce some of that school trauma and anxiety that as we know, you carry with you into adulthood and are trying to unpack your whole life. If we can take the edge off of that for future generations. I will feel like we made a difference.

How do we create emotionally safe classrooms for all kids?

I really love the idea of: how do we create emotionally safe classrooms for all kids because in my work what I've discovered is that what supports neurodivergent learners (more choice, more options, more flexibility in the environment, more of a strength based approach) benefits all kids.

You and I are a perfect example of this. We both would have benefited from a more strength based approach as kids.

So what advice would you give to educators and parents now who are trying to create more emotionally safe environments, either in their home or in their classrooms?

Emily: Yes, I think young children in school either go one way or the other. Either they take their stress in and if they're in their survival brain and they're an internalizer, they're going to look like a very compliant student.

And if they have the executive functioning and the intelligence to back that up and check all the boxes- those are the kids that we miss or that are severely masking and we don't notice them because they look “fine.”

But they could be holding in a lot of pent up anxiety and also run the risk of not figuring out who they authentically are right? Because you're not expressing who you are.

And then the other side is the kids we absolutely notice because they're the externalizers and this is where we get push back on things, we get the “noncompliant behavior,” not getting started avoidance, any type of overwhelm and aggression and arguing- all the things, all the dysregulated behaviors that we may see.

These are the kids that teachers will say: “They're oppositional when I give them a demand.” And so whenever I hear those words, I'm like, okay, let's take a step back and really get curious about what's going on with this nervous system, because these are likely not at all active choices.

This is a stress response, so there's something about the expectations. It could be the expectations of the actual academics and learning and curriculum, but it also could be the expectations of the environment in terms of the pace or the sensory processing of the environment. Or how many people are in the classroom. Or it could be any of these things are out of alignment with the skills they have to process those things, or to function in that group, or to understand that content, or to plan and get started on their own.

So what is out of alignment?

In my course, there's a visual in there where there's a ladder and we've got the expectations at the top and the skills at the bottom.

And however, big the distance is between the two- that's the anxiety the student feels and that anxiety is demonstrated in different ways, depending on the diversity of how we all express our emotions.

But if the expectations are always too high, that child is going to be living in a stress state at school.

Melissa: And shut down. Yes. So it's almost like when we can chunk it down or modify the environment in a way that reduces some of that stress and anxiety. They have more access to their thinking brain to maybe take those steps towards the end goal.

Emily: Yeah, the first thing to notice about your students or your kids is: how they navigate a space.

I think that our movement and our autonomy over our body is so individualized and so important.

As a parent and as a teacher, you know if you've got:

A sensory seeker and a kid who runs around the space and crashes into things

And you know, if you have a low energy kid or a sensory sensitive kid

You already know about how these children are overwhelmed at times, and you may not notice it until they're overwhelmed.

So having a little bit of that time and space, in actual time on the clock and also in time to feel settled in the classroom.

5 to 10 minutes of noticing how kids are moving around the space and then figuring out:

Are there kids that need to be on opposite sides of the classroom when they're working because the one is very loud and one is very sensory sensitive?

Are there kids that need to always have a job because these are the kids that ask us tons of questions.

They may be anxious.

They're always interrupting us.

That child needs structure and probably needs an independent job to be busy.

We know these things and we usually figure them out later in the year. But I talk with teachers all the time about what to do about some of the behaviors that we're seeing. And many of them are sensory based, especially with young children, meaning elementary, because many kids can be still in their sensory system more than in their cognitive mindset until up to 3rd, sometimes 4th grade if they're neurodivergent.

So in the beginning of the year, I always recommend and I've created a resource for this that's free called the Regulation Roster. It is like a class roster, but what's different about it is you write everyone's name and there are five different ways kids navigate space or the things that they need to be in a group and you categorize everyone.

And then there's a space for you to write their interests. Because when a child is needing connection, we have to observe and note and always follow what are they interested in. So it's a way for teachers to stay organized on all the different needs of students. That's the 1st thing I always recommend- having time and space to notice how kids move, notice what they seek, what they go towards.

It isn't just a coincidence that they're over there playing with that fidget. Their eyes and their body goes to what they need.

So it's shifting the mindset of instead of telling a kid not to jump, tell a kid where they can jump.

Melissa: Exactly. Create a space where they get that proprioceptive input that their body isn't conscious of, but knows they need, to jump, to regulate. It's always amazing to me because I agree with everything you're saying as far as like children's bodies intuitively know what works for them.

And I've found this time and time again, the more as adults that we get curious with:

How would you like to do that?

How does that work for you?

Do you have an idea about how we could solve this problem?

So often the responses we get from kids are spot on and what actually works for them.

Letting children be a part of the conversation of what do you need?

Emily: We as adults actually lose touch with what we need. The older we get, the more cognitive we get, the more social in terms of: Do I need to do it because it's better for the group or it's better for my family? And we unfortunately start to ignore our own needs.

Kids are really good at telling you what they need or knowing what they need. They may not be able to communicate it to you, but that's why you have to stop and watch.

Melissa: It's amazing as adults, how we have to actually go back and find a way. I love all the mindfulness practices and stuff as someone with anxiety, it's a huge part of my life because I'm constantly trying to get back into my body. Whereas as kids, I think we're naturally born in that space.

So it's a flip of what we value almost.

Understanding Intentional Behaviors vs. Stress Responses

Do you have a sense of like intentional behaviors versus a stress response?

Is there a way for parents and teachers to understand the difference between those two?

Because I think that can be very confusing.

Emily: Yes, so, when we're talking about the different regions of the brain, in terms of:

Brain stem survival state

Our limbic system/our emotional state

And our executive state being where we're calm, regulated, feel connected and can learn

What's helpful to know is that when you're not in your executive state, you probably are losing language or you're talking less if you're talking at all.

This is when kids will grunt at us and we're like: “Wow, that kid totally has words, but they're grunting at me.”

We lose our ability to solve problems.

We lose our ability to listen.

We lose our ability to say nice things.

That's more of the emotional limbic state, words are still coming out, but they're not nice and it's not something they would say if they were calm.

And so you kind of know that about your kid or about the student like, Whoa, that came out of nowhere.

It's like if you drop something on your toe and you shout something in front of your kid and you're like, Oh my gosh, I can't believe I just said that in front of my child. Well, you were in your limbic system and your words were still working, but they were not organized. They just blew out of your mouth.

When we're in our survival state:

Our brain is perceiving threat

And our body is going into shutdown.

It's going into complete survival mode and we usually lose language, which makes sense because it's not time to communicate.

Usually our digestive system can shut down. That's why kids will get stomach aches and somatic, complaints. Our pupils can dilate when we're in that sympathetic and then parasympathetic. This is all about the autonomal nervous system.

The example that I use is let's say there is an autistic child, and there's a fire drill. We don't question if we know that that child is going to have a strong, anxious sensory response to a fire drill. We do not question that that is an active choice of melting down or covering their ears. Their body is in a threat response because of the overwhelm of that. And, we can do all kinds of things to help help kids that are in sensory overwhelm responses.

But what if that response is a little bit more social in nature. So, for instance, if another student makes a kid mad and that kid responds by walking over and knocking down their tower, which appears to be on purpose, in kind of a revenge way. That kid is probably in their limbic system. They're in their emotional state. (That's like the equivalent of us saying a bad word when we drop something on our foot. Right?)

When that child is calm and regulated they may not do that, but they're angry and so they're doing that.

That would be more of an intentional behavior that's different from a stress response.

We can't teach a child to process the fire drill any easier. That's developmental and we give them accommodations until their body develops and hopefully that gets better for them, or we remove them from the situation because it feels almost cruel to expose them to that that kind of thing.

So the difference here is, if you feel like a student or your child has had an INTENTIONAL behavioral response to something that is what I would call a maladaptive response (it's not helpful. It is a response.)

I always say, if we don't teach kids coping strategies, they're going to come up with one.

Anything in a stress response is not something we would really teach yet, because that child's not capable of learning a better way developmentally yet.

They may be at some point and what we would teach in a stress response, would be a strategy.

So, let's say that autistic child with the fire drill, we could plan that there's going to be a fire drill at this time, and they know the time and they put on headphones and they walk out with their safe person. And could they more independently have those strategies?

Our goal is not to make them tolerate the stress or to handle the stress response.

With a child who has a more maladaptive behavior or coping strategy, that's not helpful. The goal is to teach them a better way.

Why Traditional Discipline Doesn’t Work for Neurotypical Brains

And this is where traditional discipline doesn't work in neurotypical brains.

In traditional discipline:

there's a consequence for not doing something that's the “right way to do it.”

And we just assume that the consequence will be enough for that child to do differently the next time.

For many neurotypical children, if they know what to do instead, they probably want to avoid the consequence so they correct their behavior and do it differently next time.

But most of our neurodivergent kids don't know what to do instead.

They're stuck if we don't teach them a better way. So if the maladaptive coping strategies are these intentional behaviors, that's our cue for: Oh, they don't know what to do when this thing happens.

They've done something like knock over their classmates tower because they're mad. The goal is not for them to never be mad. They're going to be mad sometimes.

But I need to teach them what to do when they're mad, right?

Recognizing the Tip of the (Developmental) Iceberg

Melissa: More appropriate responses when they have those feelings. That makes so much sense. I know you love Mona Dellahook, as do I, and you talk a bit about her developmental iceberg in your course and how we can really use that model to understand what's going on internally for kids. Because I think so often as parents and as teachers we see these outward behaviors and we're reacting to that behavior, right?

And sometimes we're missing the boat in really finding an effective solution or support because we're not understanding what's driving the behavior.

Emily: Yeah, and I have the privilege and the benefit of working in my therapy practice with kids 1:1. So, if I'm coming into a session where, I'm wanting to notice maybe what the parent or the teacher has reported as the tip of that iceberg.

I usually don't see it in my setting.

So if I don't see it in my office, but it's happening at school and it's happening at home, I feel like part of my job and why I love it is just being a detective.

Asking:

What time of day is it happening?

Is this child hungry, tired, constipated, nervous?

It could be relational with the family.

It could be something going on with a noise in the classroom that we can't hear because our brain is processing the sound in the space differently.

Sometimes we cannot see the reason- it is way down, down, deep under that iceberg. So we have a duty to be curious.

If we see dysregulation, there's a reason and we owe it to them to figure it out.

That's part of why I made this course and part of why I do all my professional development speaking- if nothing else, I want a teacher to leave with the feeling of: “okay, I can be curious.”

I may not know what's happening, but I can at least give that student the feeling of I'm going to keep showing up for you and figure it out, even if you can't explain it to me, or I can't figure it out yet. Growth mindset for teachers, right?

Melissa: And as a fellow recovering perfectionist, it immediately calms my nervous system to hear something like that because it's like, okay, I don't have to be perfect. I don't have to know exactly how to fix this problem. I can just be curious, like how you said going back to school, in college, you could like relax because it's like it's an experiment.

We are curious. We're learning. There's something that makes it less about we're not doing our job right or we're failing people, that sometimes causes us to shut down or feel defensive or it just doesn't serve any of us.

So I love this shifting perspective on it for everybody.

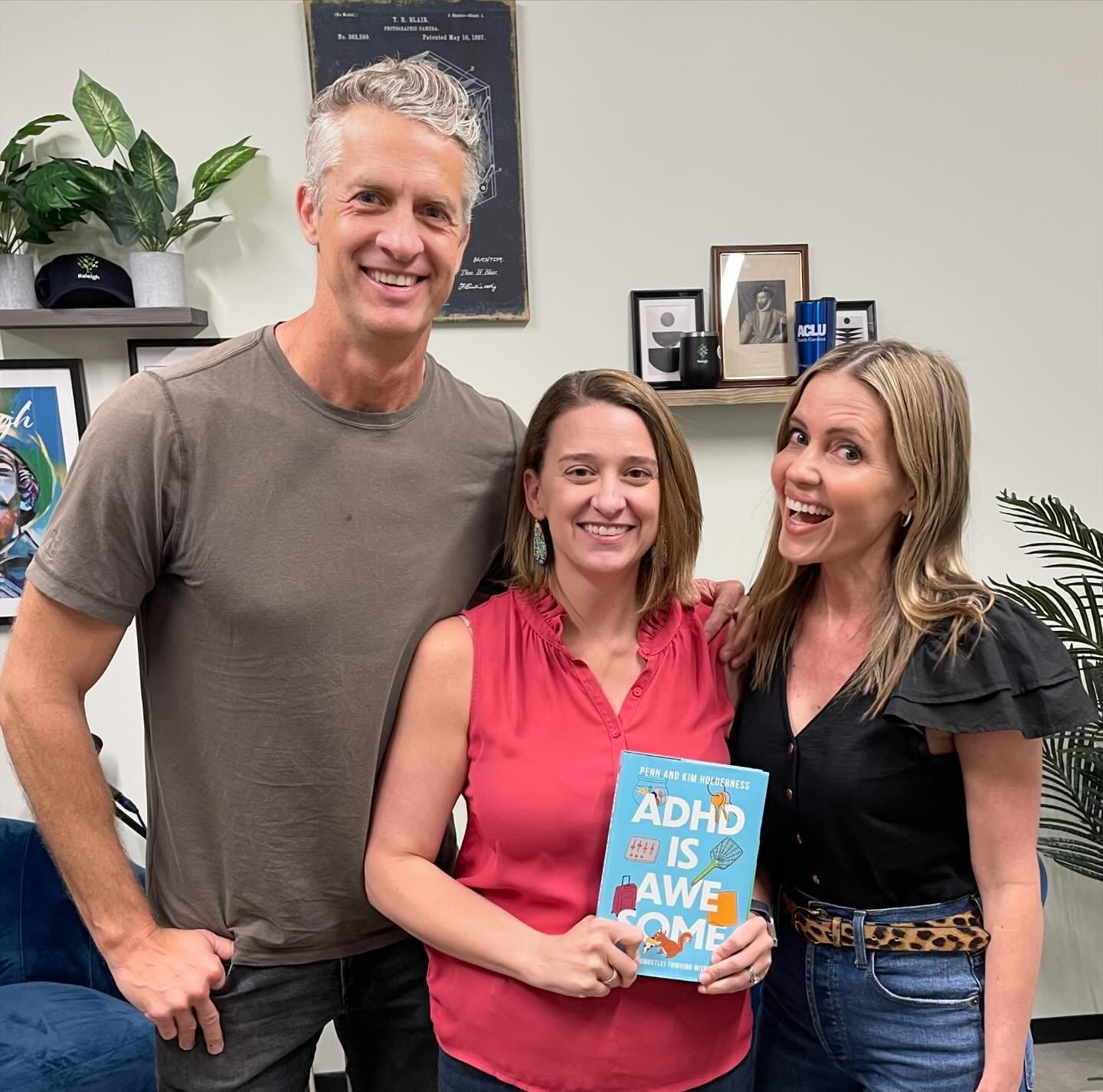

Connect with Dr. Emily